https://www.bostonglobe.com/magazine/2015/02/12/the-green-crab-problem-shall-eat-enemy/Ahtg6L87Gpxs0RMKntYAoN/story.html

European Green Crab

Carcinus maenas

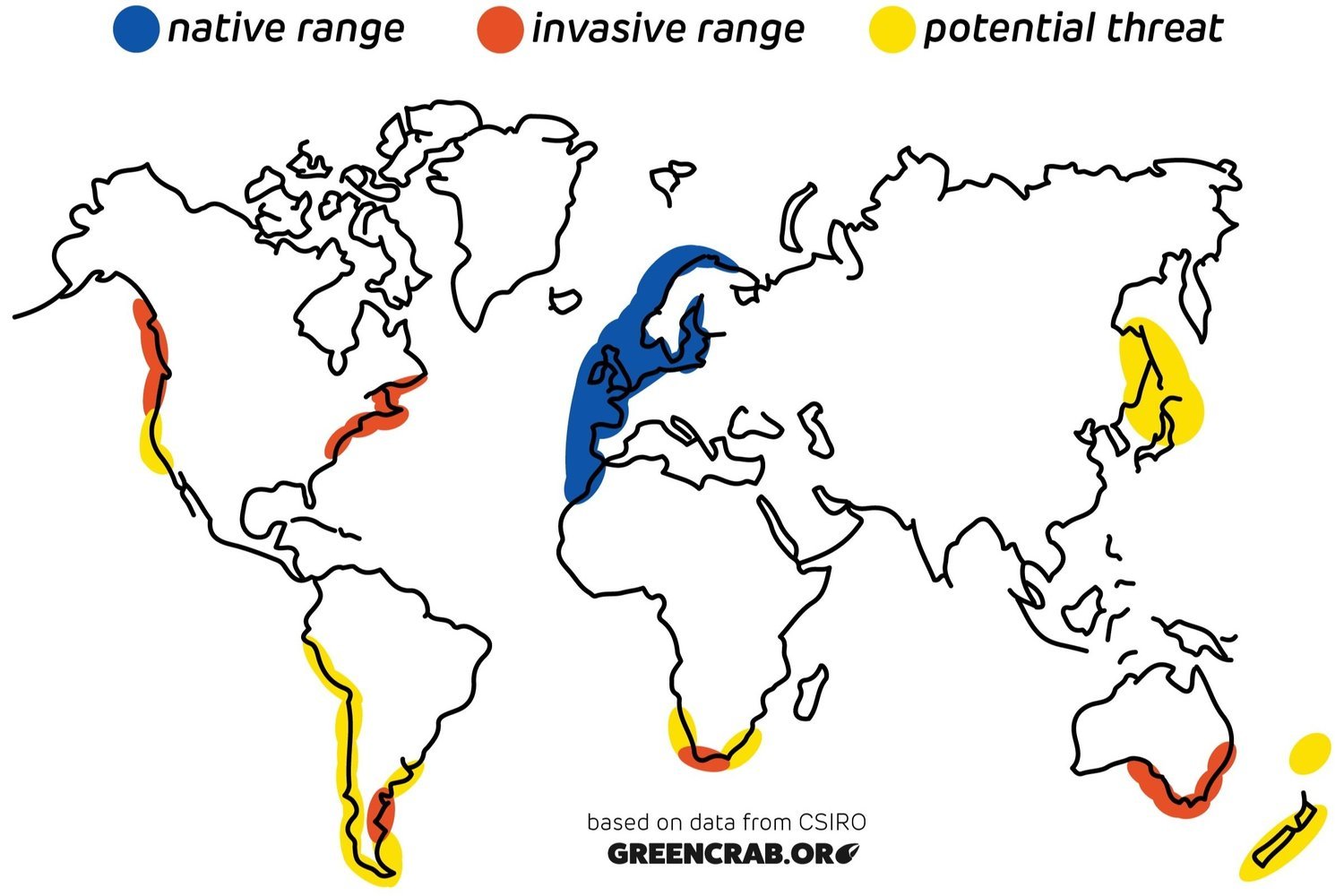

The European Green Crab is one of the most successful coastal marine invasive predators in the world. It has established populations in 5 continents. The European Green Crab was the first marine organism to be established as an aquatic nuisance species by the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force (ANSTF). Green crabs are notably damaging in coastal regions in North America while maintaining established populations in South Africa, Japan, and Australia.

Spread and distribution

The European Green Crab is native to the coasts of the Nordic and Baltic seas. The green crab has invaded numerous coastal shores including South Africa, Australia, South America, and North America. In Maine, green crabs are among the invasive species of the Maine Department of Marine Resources tracks.

On the West Coast of the United States, green crabs have been expanding their range over 750 kilometers in less than 10 years. The European Green Crab has established populations in every significant bay and estuary from Monterey Bay, California, to Grays Harbor Washington. They also have the potential to establish populations from the Gulf of Alaska to Baja California. The green crab’s invasive distribution is most-likely the result of planktonic dispersal of larval stages of the species. This is not because of the movement of shellfish products and other human activities. On the East Coast of North America, green crabs have recently continued to expand their populations to the Gulf of St. Lawrence at Prince Edward Island, Canada.

This diverse and effective spread of the green crab population hints to the green crab’s strong ability to effectively and rapidly expand their population. It’s predicted that the green crab population is to continue to expand.

identification

https://wsg.washington.edu/crabteam/greencrab/

Despite their name, European Green Crabs aren’t always distinguished by their shell color. The species’ adults have shells (carapace) that can range from dark green with yellow markings to orange or even red.

Introduction

The European Green Crab arrived at the eastern seaboard 150 years ago, originally invading New Jersey to Cape Cod, and down in the Chesapeake Bay (1879). In the early 1900s, they started their invasion northwards to Maine and throughout the Canadian coastlines of Cape Sable and Nova Scotia. The crab also has established itself as an invasive species on the west coast as well. It has been inferred that the reason for the invasion of the European Green Crab in North America is because of the species possibly crossing the Atlantic Ocean on ship’s ballast water.

Habitat

Primarily, the European Green Crab is found in soft-bottomed intertidal zones that is also favored by soft-shelled clams and other bivalve shellfish. Also, they are likely to populate rocky intertidal regions as well. Recent information has revealed that the green crab is expanding its presence into sub-tidal habitats as well.

Currently

Concerningly, the green crab population in Maine is increasing exponentially. They feed on economically-important shellfish species such as blue mussels and soft-shelled clams. Lobsters have even been found in the stomachs of green crabs and studies have shown that green crabs can outcompete lobsters and native crabs for food. This threatens Maine’s third largest wild fishery. They also are responsible for the degradation and loss of criticall nursery-habitat eelgrass beds and salt marsh habitats. The increase in the invasive green crab population correlates with the rise in ocean temperatures. A similar trend occurred in the 1950s, when the ocean temperatures rose and the green crab population increased. This increase in ocean temperature led to the devastation of the soft-shelled clam population in Maine. Fortunately, this trend reversed during the frigid winter temperatures of the 1960s, though this isn’t predicted to be replicated with the current increase in ocean temperatures caused by climate change. Currently, the Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 99% of the world’s oceans. A decrease in ocean temperatures isn’t projected in Maine’s future, meaning it’s predicted that the green crab population will continue to rise alongside ocean temperatures. Over the past few years, Maine and other New England states have seen an explosion of invasive crabs on shorelines in the spring and summer, and even into the fall.

Eelgrass bed

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/importance-eelgrass

Damage to Eelgrass Beds and Salt marshes

Eelgrass beds are a very valuable and critical habitat for many native-to-Maine and economically important species. Such eelgrass beds provide nesting, refuge, and mating and feeding areas to Maine’s vital intertidal native species. Eelgrass beds are also nutrient absorbing and protect Maine’s intertidal water quality as well. The economic value of eelgrass beds have been estimated to be $7,690 acre/year. Evidence has shown that green crabs are responsible for a 50% decline in Casco Bay’s eelgrass beds over the past few years. Green crabs are known for notoriously snipping eelgrass to make hunting prey easier.

Salt marshes, which naturally evolve over time to accommodate rising seas, alterations to hydrology, and other factors, are also negatively impacted by the invasion of green crabs in the gulf of Maine. Green crabs have been observed using cavities in the salt marsh bank creek channels. The utilization of such salt marsh cavities undermines the marsh vegetation, accelerates creek channel erosion, and reduces salt marsh area as salt marsh creeks expand

Salt marsh bank erosion caused by green crabs

https://www.wellsreserve.org/blog/green-crabs-damaging-maine-salt-marshes

biology

Green crabs can survive in environments with low oxygen levels and in varieties of salinities. They also can spawn up to 185,000 eggs at a time and their larvae can travel long distances along the water column. A single green crab female can produce to groups of eggs per year. Also, they are omnivores: they eat both plants and animals.

Threats to water quality

By impacting native shellfish populations, eelgrass beds, and salt marshes, green crabs pose a threat to the Gulf of Maine’s water quality as well. Eelgrass beds absorb wave energy and reduce re-suspension of sediments. Soft-shell clams and other bivalves filter the water by trapping pollutants. Where eelgrass beds are gone, shellfish populations have been drastically reduced, and where salt marshes are rapidly eroding, water quality is declining.

current efforts underway

While there is no viable commercial market for green crabs (yet), efforts are being developed to establish such a private commercial sector to have an economically-based incentive to deal with the invasive European Green Crab population. There is one development being made that converts the protein from green crabs into sustainable aquaculture feed for local and possibly external use. There is also investment in composting such crabs. Research has occurred at the University of Maine to produce food additive paste made from green crabs. The Department of Marine Resources is also working closely with industry, academe, and with municipal shellfish programs to monitor and contain the spread of the European Green Crab.

The Department of Marine Resources issues Green Crab Exemption permits to municipalities that want to trap or utilize other green crab removal programs. This allows for a plethora of people to participate in green crab removal activities without obtaining green crab removal permits ($38 per Maine resident) or submitting landing reports. Also, the Department of Marine Resources works with the Army Corp of Engineers as a consultant on issuing such permits in order to conduct green crab fencing projects. Fencing has proven historically to be an effective method of excluding green crabs from bivalve shellfish resource areas.

If Maine takes no serious action towards the looming threat of the exponential green crab population growth, things could become catastrophic. This would put a greater strain on soft-shelled clams, other bivalves, lobsters, eelgrass beds, salt marshes, and even our native crab populations. We must incorporate policy-based solutions to address such issues. Not taking action isn’t a solution.